THAT TAMMY RAE?

WORDS BY ABI SLONE

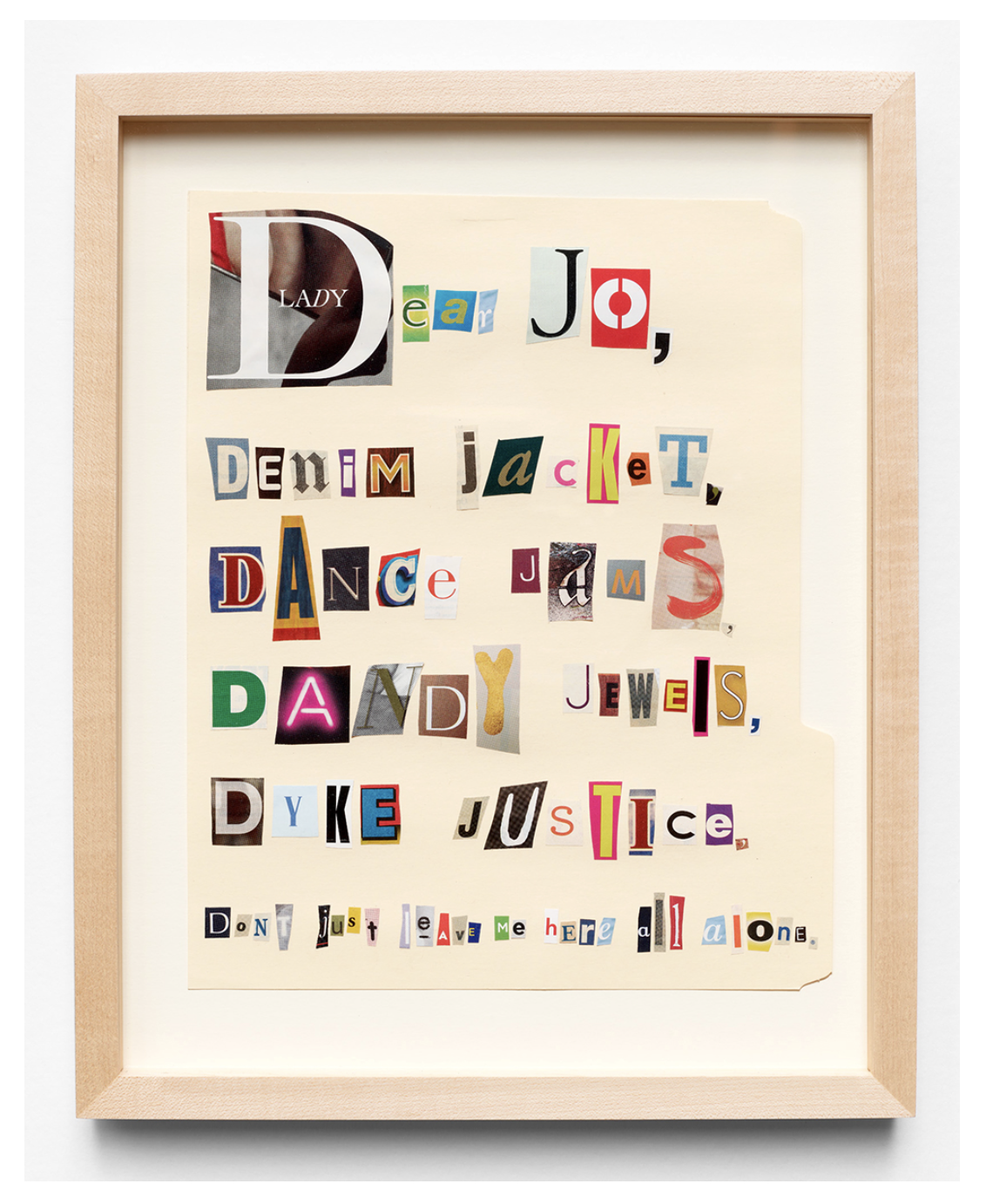

ART BY TAMMY RAE CARLAND

From top: Portrait of the Artist as the Artist, “Hannah Cullwick”, 2000; Lesbian Bed, “Untitled #5, 2002; Lesbian Bed, Untitled #3, 2002; On Becoming Billy and Katie 1964, “Untitled #1”; On Becoming Billy and Katie 1964, “Untitled #6”; Postpartum Portraits, “Rusty Love”, 2006; Live From Somewhere, “Smoke Screen”, 2013; Live From Somewhere, “Double Spot”, 2013; Live From Somewhere, “Open Mike”, 2013; What is the Question to the Answer, “A Rose is a Rose”, 2018; Dear Jo, “Don’t Just Leave me Here”, 2009; Dear Jo, “About the Photograph”, 2009.

Full disclosure. Tammy Rae Carland is part of my larger orbit. The dear heart of one of my oldest and bestest friends, I have had the pleasure and privilege of knowing her outside of her work and the things in her past and present, and no doubt, future, that make her iconic — the things that when I mention her name make people ask, “That Tammy Rae?”. From her time running Mr. Lady Records and Video, to being immortalized in more than one anthem of a generation to her work as an artist/archivist/academic, the woman whose zine donation, “Tammy Rae Carland Riot Grrrl Zine Collection”, to the Fales Library and Special Collections at NYU came in at over 5.5 linear feet continues to reinvent, reexamine and rethink who she was, who she is, and who she might become.

THE CRONING: So, because we know each other, and I tend to not Google the people I meet in my normal life ‘cause I think it’s weird and creepy, but to prepare for this interview, I had to do a bit of a TR deep dive. I came across an interview with Glen Helfand where you talked about the things you learned from your parents and how that influenced you and your work. So, if you’re good with it, let’s start at the beginning, in a way. In the interview with Helfand you said (and I’m paraphrasing here), ‘My father taught me how to never fully become, and my mother taught me how to disappear.’ Is that still something that now at this stage in your life having a different relationship to parents, parenting, history, something that's still resonates?

TAMMY RAE CARLAND: I think it does still resonate. My dad was gay, or bi. I don't know because he never fully became. He definitely had relationships with cross-dressing men [a term from the times]. He died when I was 14, and I didn't know that about him until I came out to my mom when I was in my late 20s and her response was, ‘Well, your dad was that way.’ And I was completely blown out of the water.

I thought, ‘Oh, yeah, that roommate.’ So there were a few things that sort of lined up. Just a few, not a lot. But certainly the not becoming, not fully being a realized person — whether it's generational or Catholicism or whatever it was for him. It was definitely something that was forever present in my consciousness even before I knew it. And my mother, she was never resourced or privileged enough because of her class and gender to take up space as an individual woman. So for me, my life was like an act of resistance to both of their pathways. It was a learning by default — learning by not teaching me who to be, but teaching me who not to be.

TC: Do you think that at this point in your life and career, you are more yourself than you’ve ever been? Or are there times in the past that you reflect on and you think, ‘That person, I know that person. I understand that person. I’d like to get back to that person?’ Or are you feeling, ‘I am everything I’m supposed to be, and still evolving.’

TRC: I think it’s a bit of the latter. I was thinking about it this morning. I saw my reflection and I was like ‘Who is this lady? Who is that old woman?’ In my mind I see myself as 27 to 33. I don’t know if that age is seminal for some reason in terms of my own self-awareness or becoming, but it sort of stuck. It’s not vanity, but I think that was the ideal me. I’m constantly caught off guard. It’s just so interesting. The other thing it makes me think about is the conversations I’ve been having with women friends about confidence, and not feeling as confident as I once did… I had a conversation with a therapist about this about five or six years ago and she asked, ‘Well, were you more confident or were you just naive?’ It really kind of blew my mind. Because I was just dumb, but in the best of ways. More balls out. Like ‘Who fucking cares? I don’t fucking care what you think.’ in a really youthful, you can't hurt me, I'll hurt you kind of way.

TC: Right. You had less to lose because you had less.

TRC: Exactly. And I just didn't have layered self-reflection or self-analysis. Some people will say there are three acts in life — the first 30 years, the second 30 years, and then the third 30 years. I just entered the third act this year. And even though I can resist those capitalistic theories of aging, I do see a really distinct first 30 years, second 30 years… It lines up with Saturn Returns because apparently I'm in one right now. So there's something cracking open and it feels different, less confident, but in a way that's exciting. I'm trying to have beginners mindset on things, even in my art practice.

TC: How so?

TRC: Well, I took a class with my friend Lena Wolf on colour theory and painting. I haven't painted something since I was in art school in 1983… I don’t touch those materials, and I’m not good at it. It’s something I’m not seasoned with or have any expertise in. But I’m going to make some paintings even though it’s not clear why I’m doing it.

TC: How does it feel to do something that you’re not good at, knowing that in your arsenal you have access to so many things that you are good at, or practiced at? Why the drive to pick up something and experience that “not good at” feeling? For me, it would be a source of frustration ‘cause I have a thing where I feel like I should be good at everything that I touch immediately, which is of course, completely irrational.

TRC: I have that too. So, I think it's trying to work against something that comes really natural to me, and not trying to prove something. I don’t even know if anything materially will come from this experiment, of if my gallery would be interested, or collectors will be interested, or reviewers will be interested.

I just spent 10 years in a really, really, really hard day job, an intense leadership position at a college as the vice president of academic affairs and everything in those 10 years, Monday through Friday, was completely scheduled and jam-packed. I went from meeting to meeting to meeting, conversation to conversation to conversation. Solve a problem, solve a problem, solve a problem, innovate an idea, innovate an idea. It was 60-hour weeks and my practice as an artist was just a faucet drip. It’s not like I did nothing, but I was leaning into older work and things got unearthed and reintroduced to the world which was nice but I was unable to do substantial bodies of work or have any more than an hour or two to focus at a time. So part of being able to take this class with my friend and have a beginner’s mindset was that I needed to remind myself that I don’t know everything.

I didn’t want to move into being a full-time artist with the same work grind mindset. This is the first time in my whole life, in 45 years, where I haven’t had a day job.

TC: Do you wake up at a different time?

TRC: You know, my wife and I switch off on taking one of our kids to school. So, if it’s not my day to take him to school…, today I think I slept until 9:30am, which was luxurious. It’s also the age thing, ‘Why do I wake up at 6 o'clock every fucking morning no matter what?’ I'm in a process with it.

TC: Has your style changed at all over the years? Do you still find yourself gravitating towards the same aesthetic, the same clothes you want to put on because you’re comfortable, or they make sense to you, or they represent who you are?

TRC: That’s a good one. I have very few photographs of myself as a child cuz we lost everything in a fire, and because of regular poor people stuff like being evicted and not taking stuff with you. I literally have a small envelope with pictures of me, but the youngest picture I have of myself, I’m like probably four and I have on corduroys that are too short, Converse style sneakers and a t-shirt and a cardigan… I still dress like that. So, that’s when I was four and that is still my go-to.

There have been periods in my life where I’ve gone rogue — maybe more feminine or less feminine or more edgy. And and then at a certain point, I just reverted back to my three-year-old corduroy t-shirt and a cardigan. Sometimes my kid will see a photo of me and say, ‘Whoa, Mom, look at that outfit.’ And I'm like, ‘Oh yeah, look at me. Look at I did that.’ It’s not like it wasn’t authentic, and I think it occurred to me at certain points in my life to express myself externally, but it doesn't occur to me as much anymore. I like nice things and I like to be comfortable and I love fashion and I love to absorb it and and visually consume it but it doesn't occur to me as a mode of self-expression the way it did when I was younger.

TC: It sounds like you’re meeting you, post-job, and it’s someone you know.

TRC: I'm slowly but surely starting to unpack things in my studio and figure out what my system is going to be. It’s so interesting to look at work that I made in undergraduate school in the mid-80s and be like, ‘That completely makes sense.’ I always did staged photographs. I never was a street photographer. I never did documentary work. It was always conceptual… still is.

TC: Obviously artists have periods where they were doing one thing and then move on to something else. Do you see that in your future?

TRC: Sometime I get really jealous of artists who can say, ‘I want to move to the desert and just make striped paintings for 40 years.’ There’s something about that that sounds nice — just the line. Study the line. But I am not. I am a serial person. For me, the concept drives the work — problems or ideas or things I care about that evolve and change all the time.

TC: I interviewed Missy Elliott a million years ago and I asked her the same question I’m going to ask you which is, do you ever have a second where you look around, take stock and go ‘Holy shit. Look where I landed up.’?

TRC: I think so. Certainly in my day job. I had no ambitions to be the vice president of a college… become a professor and then a chair and then a dean and then the provost. I was an accidental administrator. I had skills and people wanted me to do it, and I needed the money. Very frankly it was about securing my financial future. So in that respect, it was a surprise to me, like it happened to me and I didn't make conscious choices. But then in terms of creative practice, I think I'm less surprised because it looks a lot like it used to look when I was younger. I was very fortunate very early in my art career — I got attention, but I never made any money.

I got written about and people paid attention. I made fan zines and that got attention and so then people looked at the other things I was doing. I opened up a gallery space with eight other women and bands played there, and I booked the bands. And then eventually I started a record label and video art distribution company with a former partner. I always did these multi-layered things. I was never just an academic, or just an artist, or even an academic artist up until I had kids. I also was really supportive and producing other people’s culture and work for production. That allowed multiple ways to look at me as a cultural producer and people paid attention.

TC: Did you know at the time that what you were doing was part of a zeitgeist, or were you just doing and lots of other people around you were also doing?

TRC: I think I was just doing, and lots of other people were doing. It’s what you did. You didn’t scroll on your phone, you made something — I had pen pals and zines and particularly as a young queer and going to college in a small town and coming from a small town that's just sort of how I found my people, my community, dates… all of that stuff.

In many ways I suppose I did think it was significant because I saved a lot of stuff. I had 400 zines that I donated to the Fales collection at NYU [in 2011]. So it’s either I knew enough to keep that stuff that was significant, or that's just growing up poor. With Mr. Lady, the record label, I did think it was important. I didn’t think it was the most important thing in my life, or world, but I did think it was important at a particular time in history. We were exclusively putting out work by queer-identified, and feminist-identified, punk bands.

TC: It was a game changer, and not only for you and those it touched, but it had such a ripple effect. And it still resonates so much culturally. Right now I’m sitting in this place where I’m looking at what’s bubbling. I don’t know how authentic it is or whether I’ve fallen into a convenient algorithm, or if there really is a sweep of ‘women of a certain age’ making work/art around being of a certain age.

TRC: I went into full-blown menopause at 50, ten years ago, and the conversation now is really different than it was. And nobody was really talking about perimenopause. Even when I went to my doctor and said, ‘I think I’m in menopause.’ She said, ‘No, you’re still bleeding. You’re not in menopause until you stop bleeding.’ but there was all of the other indicators — Can’t sleep. Wake up every 20 minutes. Hot flashes. Depression. Anxiety…. Maybe it’s crossing my feed because I am paying attention, but it is different now.

TC: Do you think that it will impact the cultural production of women who are impacted by it?

TRC: I think it’s a really interesting question and I’m super curious because there are some general truths such as, ‘I don't give a fuck anymore what people think.’ kind of attitude. And so what do people make if they don’t care about the critique, right? If the critique is superficial to them, what kind of opening is that? That’s kind of an amazing idea.